Minification isn't obfuscation - Claude Code proves it

This is the first in a series of three articles I'm going to be releasing over the holiday season, on how I think agents are completely reshaping software engineering beyond pure productivity enhancements. If you'd like to get notified when they come out, please subscribe to my newsletter or RSS feed.

Please respect terms of service for the software you inspect if it is external to your organisation. Many (but not all) licenses have exceptions for legitimate security research, and I think this approach has great potential in shining the light on the millions of lines of opaque JavaScript we run these days for good.

One of my passions is web performance, which inevitably means spending a lot of time staring at minified source code. Whether you're trying to figure out why a bundle is bloated or debugging a production issue without source maps, anyone in the performance space knows the particular pain of reading minified JavaScript.

Of course, hopefully most software engineers know that the minification process that JavaScript uses doesn't actually secure anything. It just makes it very hard to read. And with the advent of React bundles in the megabytes you could easily spend a few days getting fully to grips with just one bundle. Fully reverse-engineering a production bundle used to take a specialised engineer days or weeks of masochistic effort.

That effort barrier vanished.

The shift

I realised somewhat by accident that LLMs can read minified JS like prose some years ago, by copying and pasting the wrong code into gpt-3.5 way back when. However, they had significant drawbacks (minified JS absolutely chews through tokens). Agents really have dramatically changed the calculus on this.

One of the most interesting parts of experimentation I've been doing recently is combining somewhat arcane software engineering techniques with agents. Combining these firstly makes me realise how much low hanging fruit is still out there with agents, and secondly how you can mitigate a lot of the context window limitations using them.

ASTs + agents

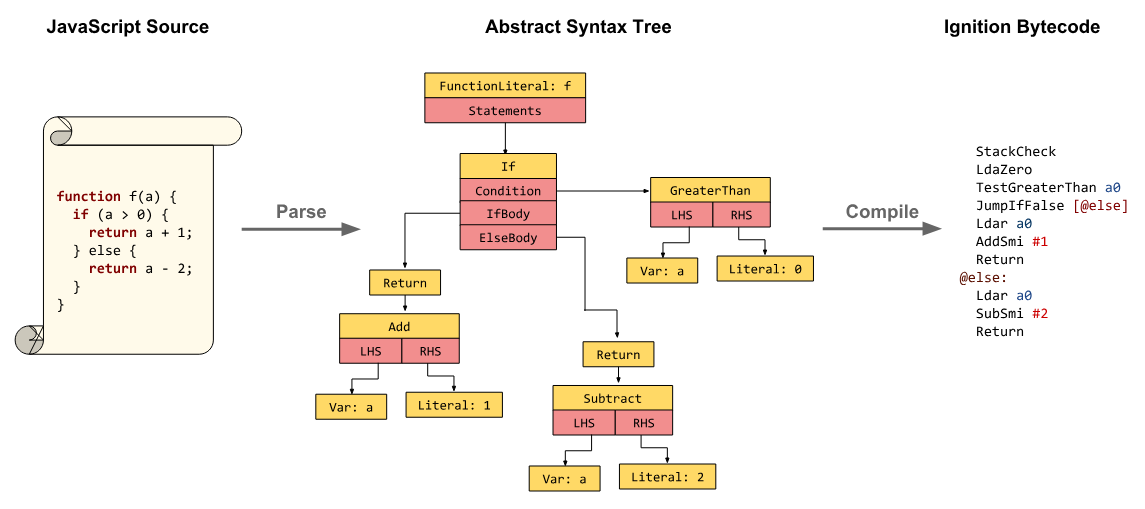

Abstract syntax trees express code as a tree structure that's easy to traverse and manipulate programmatically. Your browser actually makes ASTs out of every single script on every page you visit, in the background. They're one stage in turning code like JavaScript into fast, optimized machine code, enabling developers to do things like ship tens of megabytes of JS source to make a to-do list app (I jest, I think!).

There is loads more interesting material about this on the v8 blog.

Minification strips away variable names, but it cannot strip away logical structure. As the diagram shows, a Return node or an If statement remains constant regardless of whether a variable is named processPayment or z.

This got me thinking. What if we took an AST parser, like acorn and told Claude Code to delve into some minified source code with it?

Pulling it all together

I was curious to compare two versions of a popular minified npm package to see what I could pull out. This is many megabytes of minified JS, and with the recent npm supply chain attacks, that makes me nervous - what was hiding in there?

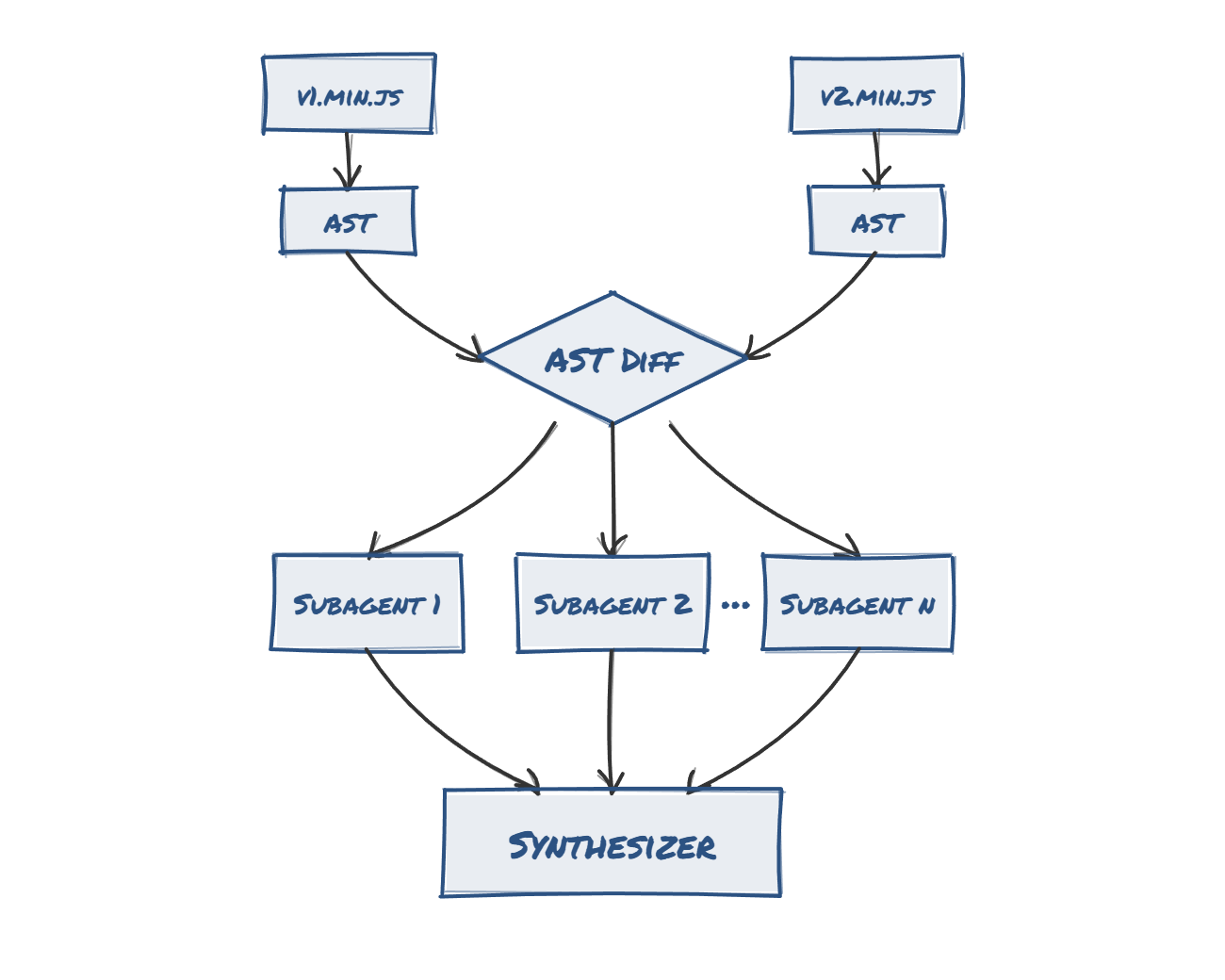

I started by grabbing the two most recent versions using npm view and npm pack. I then told Claude Code to generate ASTs for both versions, process the diffed AST, spin up 10 subagents to focus on the most interesting parts, and synthesise everything into a final report.

The bottleneck for LLMs has always been context windows and token costs for large files. By using ASTs, we can get a logical representation of the entire file - (usually) fitting in the context window for each subagent - while also leaving space for each subagent to investigate its assigned logical branch.

The results were eye-opening. The 10 subagents give you over a million tokens of combined context window, and the diffed AST gives them a solid starting point.

A quick scan through the report the Claude Code created in less than 10 minutes included:

- Feature flags and unreleased functionality

- Logging and telemetry details

- Internal architecture details not meant to be public-facing

It was almost as good as running it against the actual source code of the product.

This applies to everything you ship

Keep in mind it is not just npm packages that can quickly be reverse engineered like this - nearly every React based website will tend to push all of the frontend code down to the user. It may be chunked, but an agent can usually quickly find the missing chunks. And most importantly: people do not selectively secure the chunks themselves, or at least I haven't come across anyone doing this.

So this effectively means a user can recreate your entire source code of your frontend web application without even a login (assuming that the login page itself is in the app - it's a perfect entry point).

Obviously they won't be able to access any data or APIs - assuming they are secured properly - but be aware that malicious parties can and I'm sure are doing this to get an understanding of your frontend.

My recommendations

This was always possible - this isn't a sophisticated new approach to evaluating code. However, going through an enormous JavaScript bundle used to take weeks. Now it takes minutes.

My recommendation if you believe you have sensitive IP - think functionality or algorithms, not API keys[1] - in your frontend is to start rethinking how you deploy this. You could secure your chunks so only users with a valid access token can access them, assuming you trust your users. You could split sensitive parts of the app off. Or there's the nuclear option: move code out of the frontend to the backend, like the good old days.

Obfuscation was never security - but it used to be effort. Not anymore.

Obviously, don't ship production API keys in your client side bundle. But a lot of people will ship their entire A/B testing framework, with every inactive and active test detailed. This is probably quite commercially sensitive and will give your entire roadmap away if you are not careful. ↩︎