Are we dismissing AI spend before the 6x lands?

You've heard the new narrative: AI scaling hit a wall, the capex is insane, the returns aren't there. But the critics are judging models trained on last-gen hardware. There's a 6x wave of compute already allocated - and it's just starting to produce results.

This post looks at how much compute is actually coming online - and the early signs of what it is achieving.

The 6x

Morgan Stanley did some excellent research looking at CoWoS (Chip-on-Wafer-on-Substrate) allocations for TSMC. CoWoS is TSMC's advanced 2.5D chip packaging technology and is used for nearly all leading silicon in artificial intelligence:

| Customer | 2023 | 2024 | 2025e | 2026e | 2026 Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA | 53 | 200 | 425 | 595 | 60% |

| Broadcom | 23 | 68 | 85 | 150 | 15% |

| AMD | 7 | 40 | 50 | 105 | 11% |

| AWS + Alchip | 9 | 16 | 5 | 50 | 5% |

| Marvell | 1 | 18 | 75 | 55 | 6% |

| Intel Habana | 0 | 7 | 9 | 0 | 0% |

| GUC | 1 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 1% |

| MediaTek | - | - | - | 20 | 2% |

| Others | 20 | 10 | 19 | 15 | 2% |

| Total | 117 | 370 | 670 | 1000 |

Firstly, we can see that total supply is estimated to go from 117,000 wafers to 1 million wafers, in just 4 years, with NVIDIA taking the lion's share of the supply. Interestingly though, Broadcom (which produces Google's TPUs) is taking 15% of that capacity, with AMD growing 15x for their MI300/MI400 series of AI chips.

This doesn't tell us the total story though - as chips are continually improving in FLOPs/mm² of wafer.

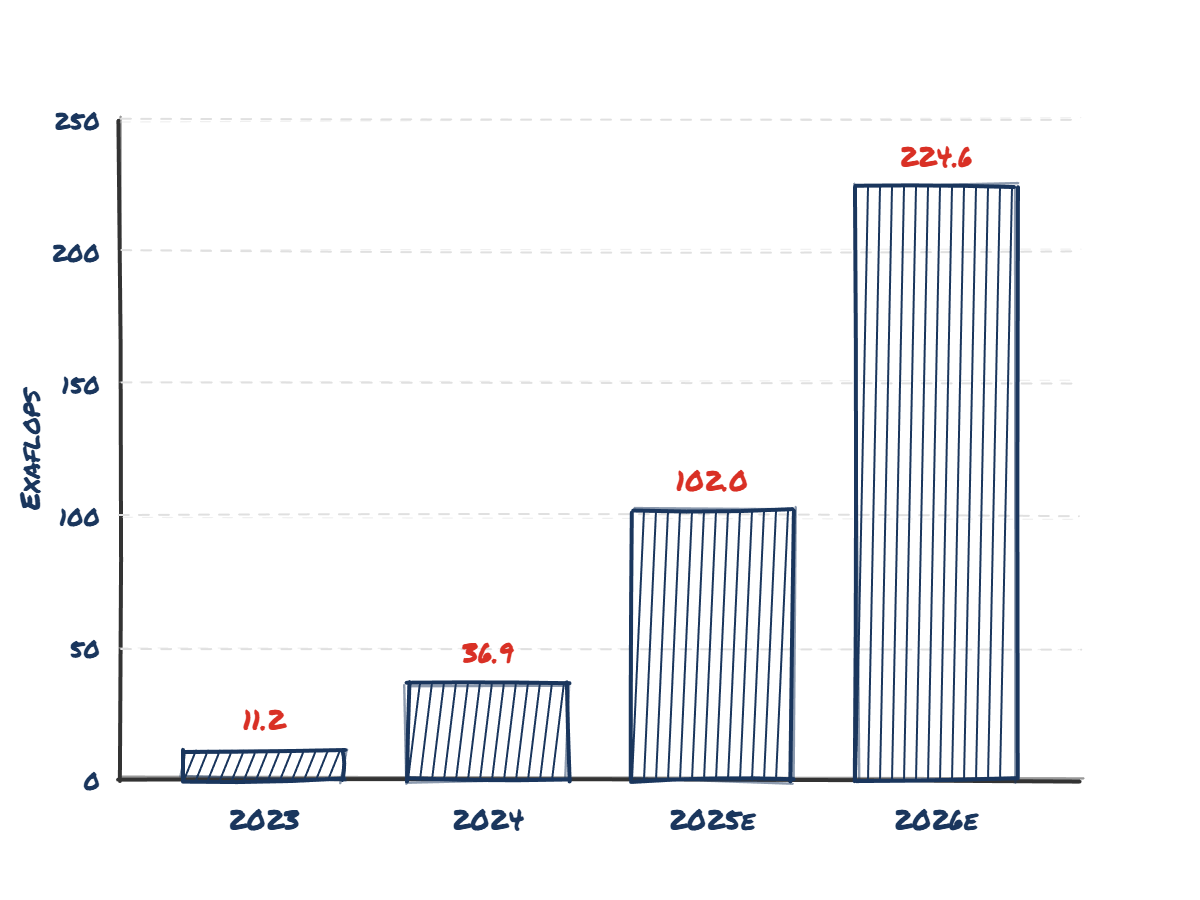

I did some napkin math[1] to try and convert this into exaFLOPs. This is a lot of guesswork on shipment mix, but I believe it should be roughly in the right ballpark:

| Vendor | 2023 | 2024 | 2025e | 2026e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nvidia | 5.7 | 23.1 | 58.4 | 99.2 |

| AMD | 0.06 | 0.94 | 2.30 | 8.86 |

| Google TPU | 0.32 | 1.39 | 4.34 | 12.98 |

| AWS Trainium | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 1.52 |

| TOTAL | 6.16 | 25.7 | 65.2 | 122.6 |

Note the Google TPU stats assume a very aggressive ramp from Broadcom, which is somewhat in question. Again, this is napkin math.

AI silicon flow is increasing dramatically - and really starts gathering steam into 2026.

If we look at cumulative installs, we start seeing a huge amount of exaFLOPs available across the globe - with a roughly 6x increase in global AI chip capacity between 2024 and 2026e.

It's difficult to undersell the implications of this growth. Between ChatGPT first launching and the end of 2026, the world will have nearly 50x more compute installed and available for us. To push an overused analogy arguably too far, the initial build of railways in the UK and US were closer to 10x over 10 years. This level of infrastructure buildout hasn't really been seen before in human history - probably WW2 military spend is the only thing that surpasses it as a proportion of GDP in the Western world.

The lag

Having said all that, there is a significant lag between a chip being finished with TSMC and it coming online - probably at least a month in absolutely ideal conditions. However, there have been significant delays with getting the latest GB200 series of AI accelerators as they require liquid cooling - which previous generations didn't. There have been a lot of rumours that this has been extremely difficult to get right, with widespread reports of overheating and leaks from the liquid cooling system delaying the rollout of this generation of AI accelerators from Nvidia.

This doesn't even get into the serious power capacity constraints the datacentre industry is currently battling - a million wafers worth of Blackwell-class silicon implies a need for gigawatts of new power capacity. This physical bottleneck is likely to be the true governor on how fast that '2026e' column actually comes online.

On top of this - the even larger delay is from when a chip gets installed and powered on in a datacentre facility to training finishing. It's likely this process takes at least 6 months end to end - assuming no major problems or difficulties.

So when we look at 'current' models - we are looking really in the past, probably 12 months or so all things being equal. When I wrote this blog at the end of 2025 we're really just seeing the results of 2024's cumulative infrastructure buildout.

Inference

It's very important to point out though that not all of this compute is being allocated towards training. Proportionally more and more will be allocated to inference to serve current customers. However, at off peak times I'm sure that the big AI players are dedicating a lot of this spare inference compute allocation to new techniques like agentic reinforcement learning - which can be easily checkpointed and done "off peak".

And let's not forget that an enormous amount of compute still is going to be allocated to training. Sam Altman has said in a recent interview that OpenAI would be profitable if it wasn't for training - no doubt the cost of researchers plays a big part, but compute has to be a huge part of the expenditure there.

Why I'm so excited, and to be honest, scared

Two models have really caught my eye recently - Opus 4.5 and Gemini 3. I wrote an article a few weeks ago delving into them if you're interested to learn more, but the quick summary is that Opus 4.5 is a step change in terms of software engineering and Gemini 3 has graphic/UI design skills far ahead of other models.

A month or so later, I really agree with what I wrote there - while the benchmark scores were impressive, they massively undersell what a giant leap Opus 4.5 has been. Combined with Claude Code I've found that it really can do 30 minutes+ of software engineering with minimal (or no) babysitting. This is a step change from Anthropic's previous Sonnet 4.5 model - which required me to constantly interrupt its execution to correct its approach.

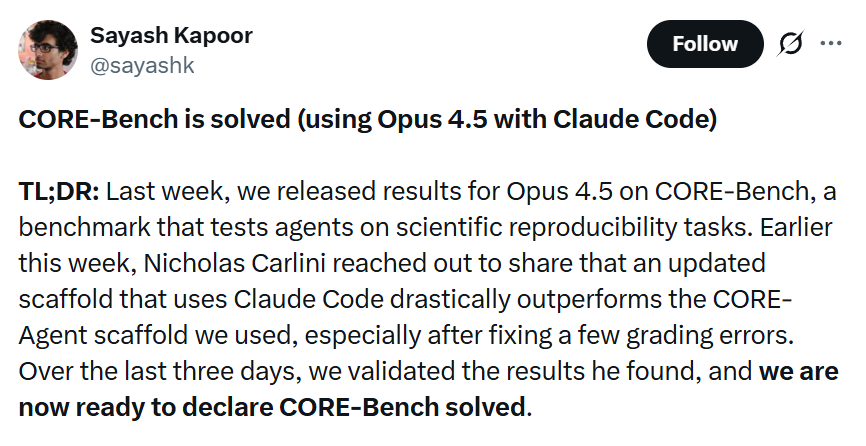

I've noticed two other more quantitatively sound approaches also backing up what I'm anecdotally seeing. Firstly, one of Princeton's HAL agent benchmarks has been "solved" by the combination of Opus 4.5 and Claude Code:

Opus 4.5 + Claude Code effectively solving the benchmark, a massive jump from the previous SOTA.

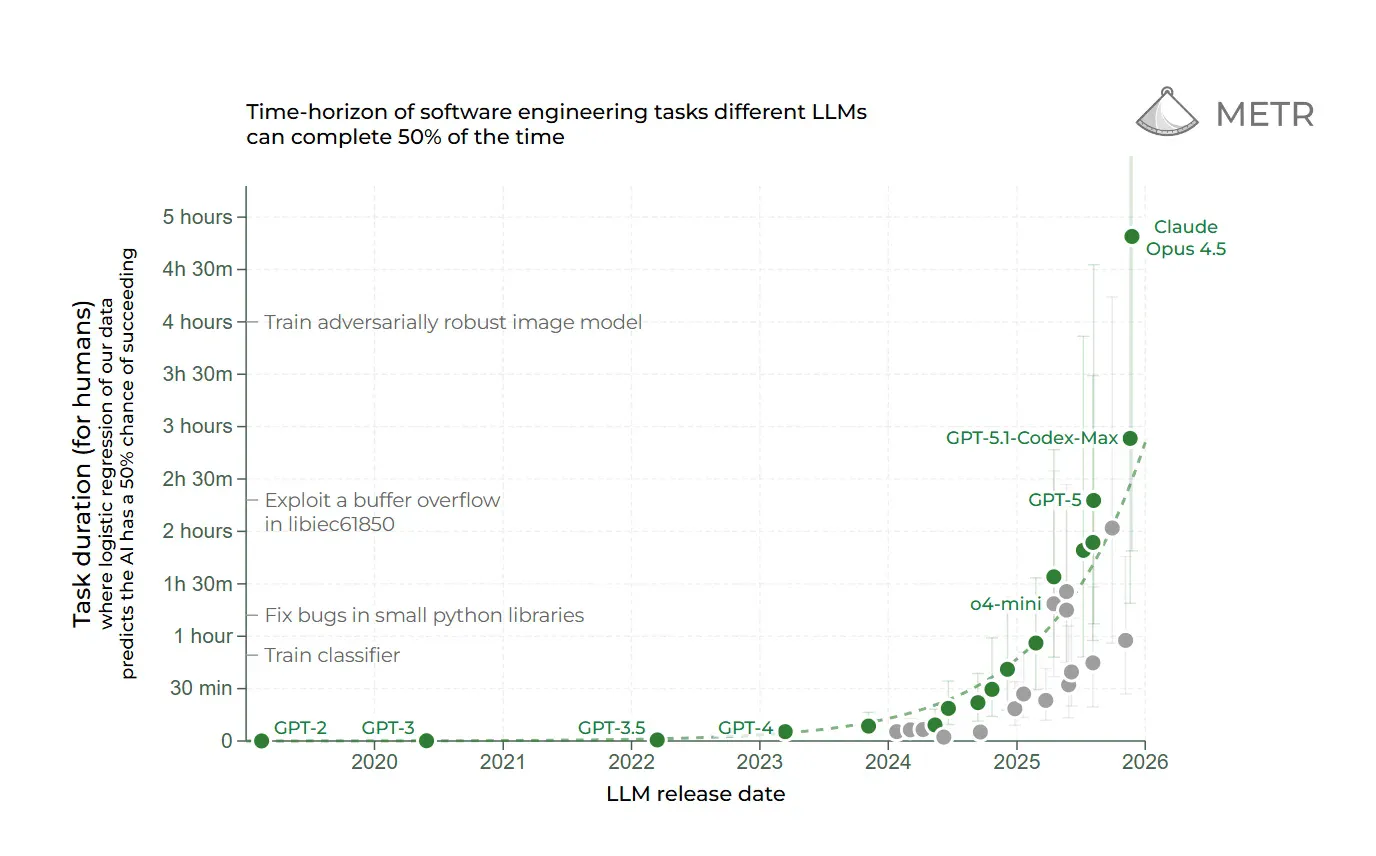

Secondly, METR has been doing some fascinating work on seeing how long various models can operate on successfully. We're starting to see an enormous leap forward on this - with Opus 4.5 managing to complete software engineering tasks that would take a human 4+ hours successfully in over 50% of cases.

Note the 50%+ success rate on tasks that take humans 4+ hours.

Now, correlation doesn't equal causation, but it's hard to not notice the parallels between the performance here and the availability of compute.

But if you look closely at the timelines, you realise that this performance isn't the result of the massive wave of compute I just described. It's actually the result of the trickle that came before it.

The zettascale future

Look at the "Cumulative Installs" for 2024 versus 2026 in my table above.

Because of the installation and training lag I described earlier, Opus 4.5 and Gemini 3 were likely trained on the 2024 install base. They are the product of roughly ~36 exaFLOPs of global capacity.

We are looking at these PhD-level engineering capabilities and assuming they are the result of the current AI hype cycle. They aren't. They are the result of the infrastructure that was ordered before the mania truly set in.

The 100+ exaFLOPs coming online in 2025 and the 220+ in 2026? That compute hasn't even finished a training run yet.

If Opus 4.5 is what we get from the 'trickle' of 2024 compute, what happens when the 'flood' of 2026 infrastructure actually finishes training the next generation? By 2030, if trends continue, we'll have nearly 30x more - a zettaFLOP (1021 FLOPs). The scaling debate is about to get a lot more uncomfortable.

Assumptions:

- Nvidia: 2024 mix was 70% H100, 30% Blackwell; 2025 is 20% H200, 80% Blackwell; 2026 is 30% Blackwell, 70% Rubin

- AMD: Shifts from MI300X to MI350/400

- Google: Moves from v5p/v6e to v7

- I also attempted to convert wafer size to each company's published or rumoured sizing (to estimate accelerators per wafer)