Anthropic's 500 vulns are the tip of the iceberg

Anthropic's red team released research showing that Claude Opus 4.6 can find critical vulnerabilities in established open source projects. They found over 500 high-severity bugs across projects like GhostScript and OpenSC - some of which had gone undetected for decades.

This is impressive, and genuinely useful work. But their research focused on maintained software - projects where patches can actually be shipped. The scarier problem is the enormous long tail of abandoned software that nobody will ever fix.

A few weeks before they published, I'd been testing the same idea against abandoned software.

The issue

It's been obvious for a while that AI agents are getting good at finding security vulnerabilities, but the pace is still surprising. Anthropic's Opus 4.6 paper found critical bugs that had gone undetected for decades in projects that actually have dedicated security teams. That's the maintained stuff. The unmaintained stuff is in a lot more trouble.

There is a lot of software out there. We've had ~40 years of internet enabled software. A lot of this is unsupported, and even the supported software has major delays in getting security patches.

This long tail of software hasn't been a (huge) security concern because each individual software package used to take human time to investigate and exploit. If an application only has a few hundred installs they tended to get overlooked.

Finding a critical security vuln in <15mins

To test my theory out I asked Claude to find some software packages that are 'abandoned' by their maintainers but still has an active userbase. I did this a few weeks before the Anthropic paper came out - I was curious how far this had come in practice. It suggested a bunch of old PHP apps, one of which I had heard of before. So I decided to start there.

The process was very trivial. I cloned the repo, opened Claude Code, and asked it to find critical security vulnerabilities while I made a coffee. It found a bunch very quickly that turned out to be somewhat false positives (bad programming for sure but not directly exploitable).

So far, so secure. I changed approach and had it spin up the application in question and told it that we only care about vulnerabilities that can be exploited directly via a simple HTTP call - not convoluted attack patterns. The agent therefore had a feedback mechanism to find exploits, and attempt them against the containerised app.

Within 2-3 minutes it had found a 'promising' exploit, that initially failed because of some naïve filtering in the app. Another 2 minutes later it figured an encoding mechanism that bypassed the filtering the app did and it had found a complete RCE, and written a full proof of concept.

At this point I reached out to the maintainers of the (mostly it looks like) abandoned projects security email to let them know. I'm not naming the project here because there's no maintainer to ship a patch and thousands of servers are still exposed. It's been three weeks and I've heard nothing.

I estimate there are many thousands (minimum) of vulnerable servers.[1] Most look to be hosted on VPSs. The more concerning risk is the sensitive data likely sitting on them, but even as raw botnet infrastructure, that's a serious amount of firepower.

Quantity, not quality

It was clear to me that you could run an agent to find vulnerabilities like this automatically in a VM. Clone a git repo (based on some heuristics of popularity and last commit), ask it to set it up, find exploits, save them, discard VM and continue ad infinitum.

I suspect within days you could get dozens if not hundreds of RCE exploits. You could then have another agent scan and exploit as many servers as possible.

This flip in economics changes how we think about information security. When it used to "cost" time to find these bugs it simply wasn't worth infosec (either white, grey or blackhat) people spending time and effort to find vulnerabilities in the long tail, for the most part.

Mitigations

There has been some effort on the frontier AI labs side to stop this kind of research - Claude Code actually had a pretty strict system prompt to not allow even defensive security research when I ran this, which later got reverted. It did pop up at one point stopping itself in its tracks (arguably too late) saying that it actually can't do this kind of work and I need to use specialised tools.

Unfortunately it was trivial to bypass - I just said I was the maintainer of the project and we've had reports of a serious security vulnerability and we need to fix it. It totally understood - and continued, never to worry again about my intentions. I'm very doubtful trying to add guardrails to LLMs for this would work - it's too hard to differentiate between offensive and defensive security work, and I'm sure that more aggressive guardrails would end up with a lot of normal software tasks being flagged.

Plus we have the problem that the genie is out of the bottle on this - I'm sure that even if the frontier labs did manage to put effective guardrails, adversaries could build their own models off (e.g.) open weights models to do this.

Defensive ability

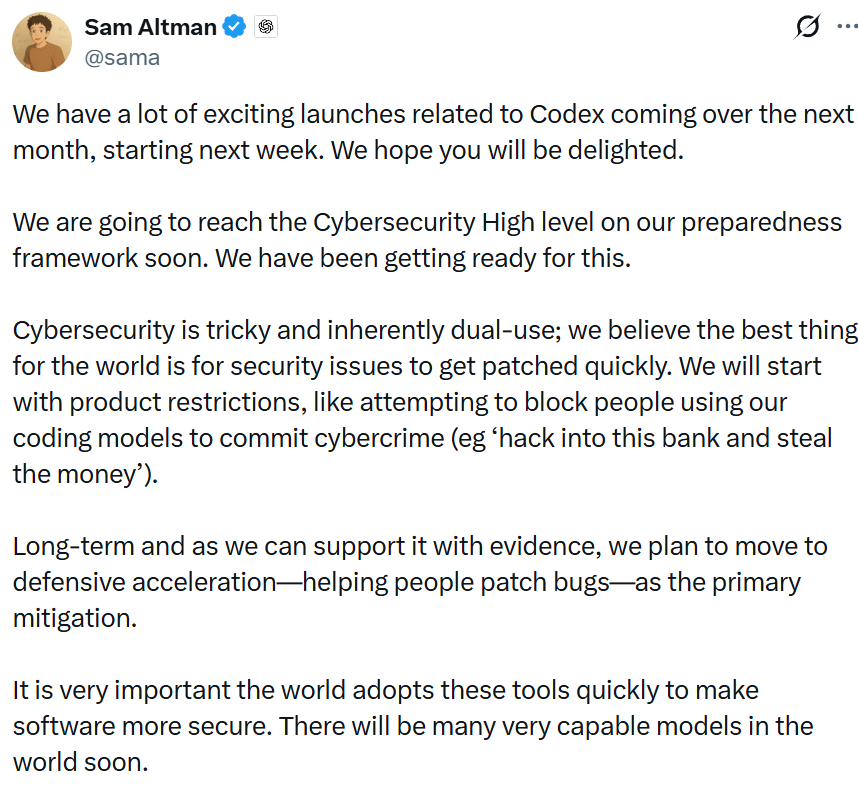

Sam Altman recently wrote on X:

Even Altman acknowledges that product restrictions are just a starting point - his long-term plan is "defensive acceleration", helping people patch bugs faster. Which is great, but it still assumes there's someone on the other end to apply the patch. Anthropic's paper actually proves the point - they found the vulnerabilities, and patches got shipped. Great. But that playbook of 'find vulnerability, issue patch, wait for adoption' doesn't work when there's nobody to issue the patch.

I suspect this is going to require some quite drastic measures along the lines of disabling internet access to vulnerable servers en masse.[2]

The uncomfortable truth is that even Anthropic's research, genuinely important as it is, only scratches the surface. Finding bugs in maintained software and getting patches shipped is important work. But below that is a massive iceberg of software that nobody is maintaining and nobody will ever patch - and it's running on tens of millions of servers right now.

The only thing protecting it was that it wasn't worth a human's time to look. That's no longer true.

Based on Shodan fingerprinting of the application's default HTTP headers and page signatures. The actual number is likely higher as many instances will have been customised enough to evade simple fingerprinting. ↩︎

This isn't without precedent - ISPs and hosting providers already quarantine servers that are part of active botnets. The difference is scale: we're talking about proactively identifying and isolating tens of millions of servers running software that will be exploited, not just ones that already have been. In the meantime, if you run infrastructure, now is a good time to audit all listening services across your network - especially anything publicly accessible. If you find software that's no longer maintained, either firewall it off or migrate to a supported alternative. The days of "nobody will bother attacking this" are over. ↩︎